At first glance, it is not clear what kind of document we are looking at. On this page, learn about the materials and techniques used to make the documents, seventeenth-century handwriting, and the process of transcription and translation that not only let us read the text as written but understand it.

Material Cultures

The materiality of the documents in the Lee Collection have a lot to teach us about the production and preservation of important legal texts.

How was each document made?

These documents are made of animal skin, parchment or vellum. After preparation (removing hair, stretching, soaking, drying, etc), the skin is likely to survive as long as the information in the document is needed.

Over the centuries, however, documents show wear and tear. Ink fades, folds or rubbing erase words, and other damage can occur. Collections managers create condition reports to identify needs for preservation. Check out condition reports for two of our documents.

Vellum documents are tough. In this detail, you can see a line of pin-pricks Vellum documents are tough. In this detail, you can see a line of pin-pricks down the side of the Wentworth will. Scribes made these holes on left and right to prepare for ruling to guide writers along straight lines.

See the British Library’s “How to Make a Medieval Manuscript” page to learn more about pen, paper and ink!

What tools put words to page?

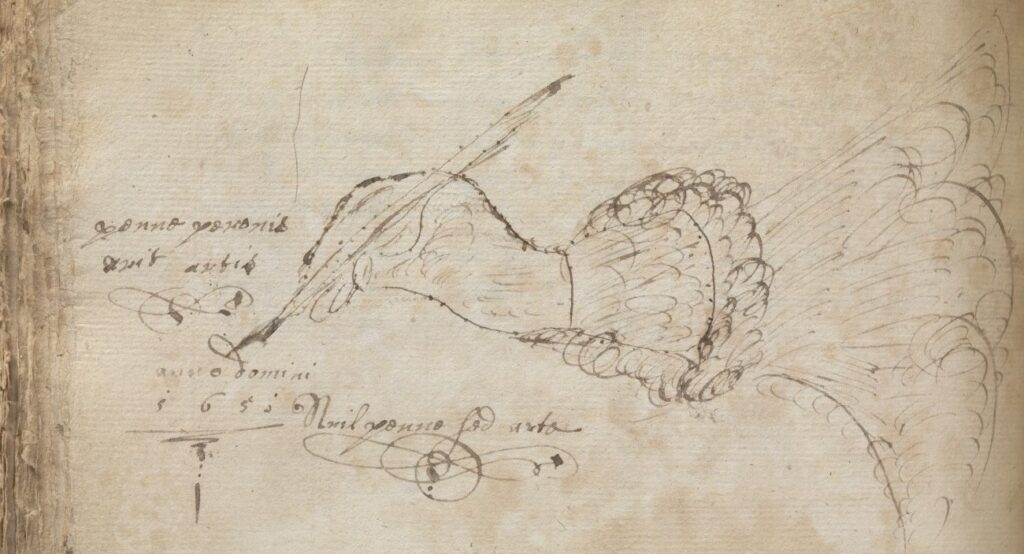

Pen and ink were the magic combination scribes used to write.

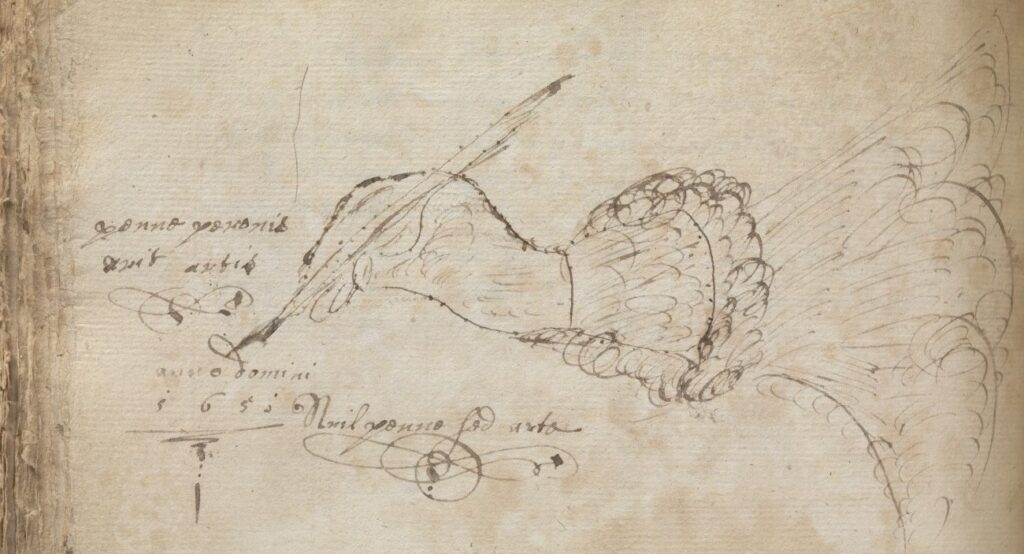

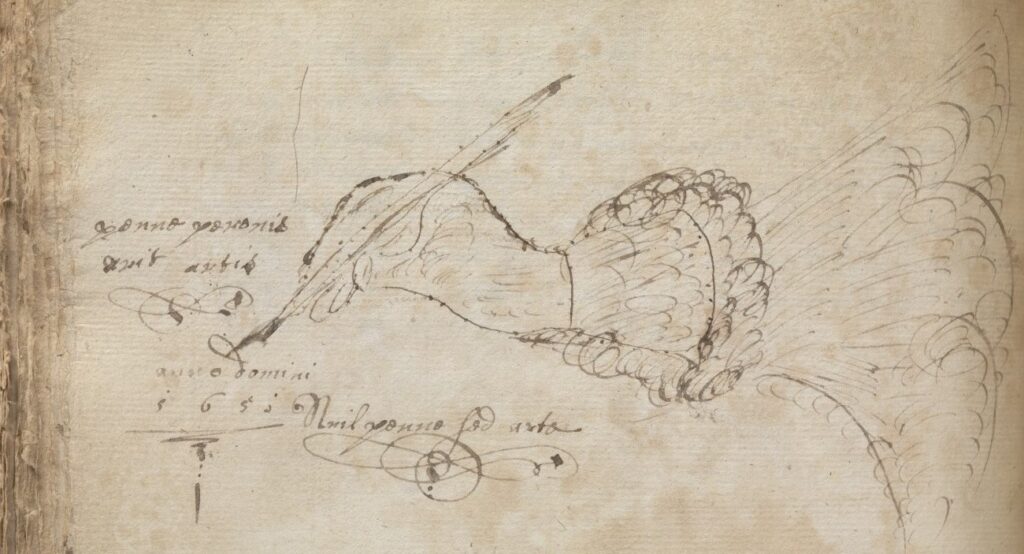

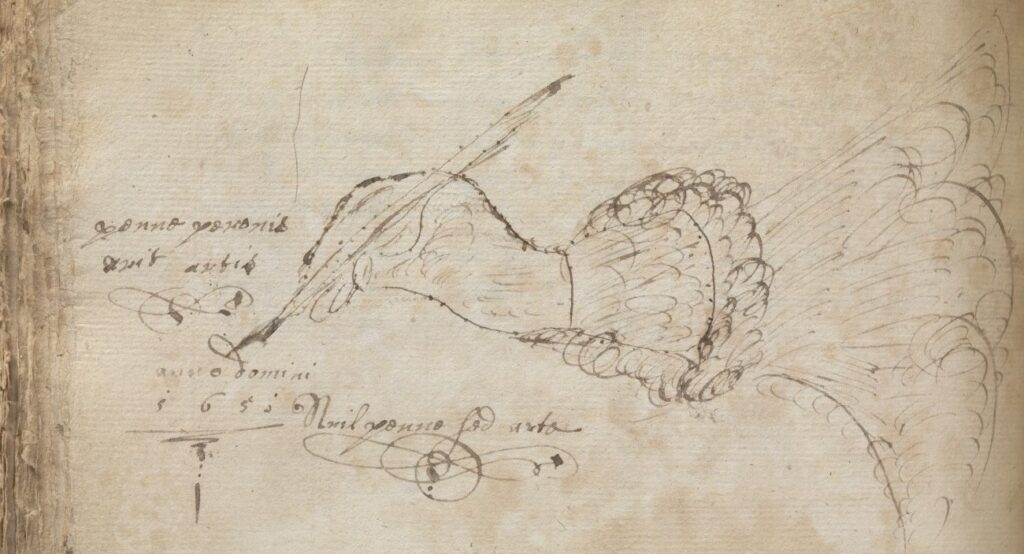

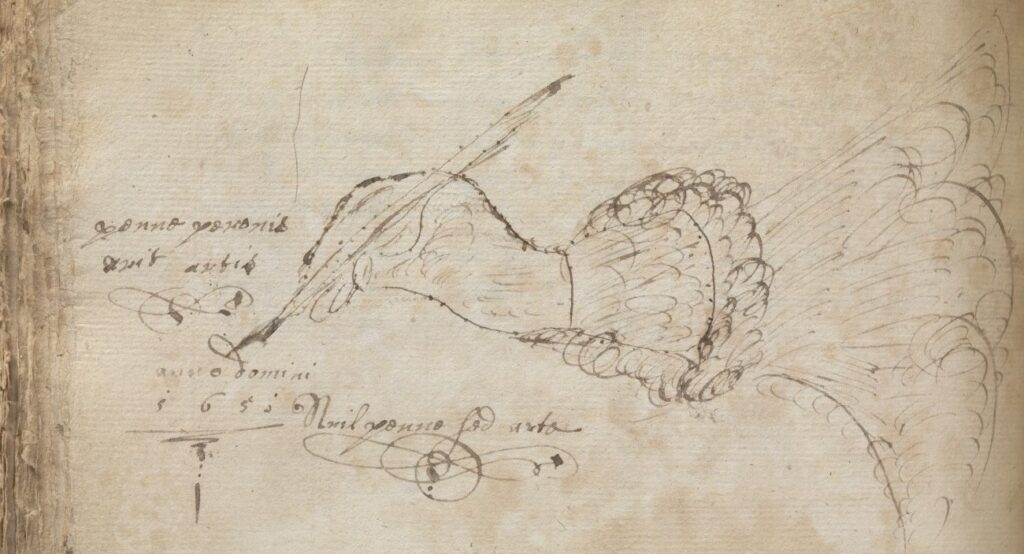

Quill pens were made from feathers from bigger birds including swans and geese. After sharpening the tip, a user would make a hollow above it to hold ink. A bigger feather held more ink!

Goose feather pens, 18th c. Chemung County Historical Society

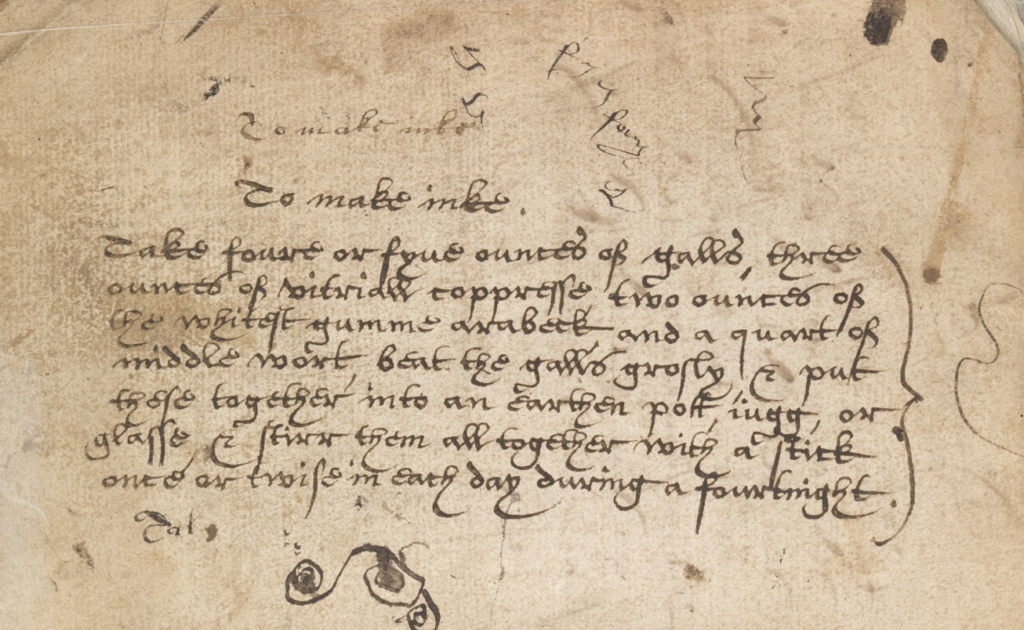

Ink was also hand made. Recipes for black “iron gall” ink taken from a seventeenth-century English copybook (held at Yale University) list key ingredients as: oak galls, gum Arabic, and “coppresse” or vitriol. Britain had many oaks. Oak Galls, Forestry and Land, Scotland

Who wrote each text and in what handwriting?

Many of the collection’s documents are written in secretary hand by clerks and notary publics. Developed in the late 15th century, this cursive handwriting style was popular with secretaries, scribes and clerks who drafted legal documents. A flowing text, which joined letters, was faster and easier for writing than block letter writing, for which they had to lift the quill from parchment.

A recipe for ink in secretary hand comes from a scribe’s copy book (it is one of several recipes for black ink; he also includes recipes for white and red ink.

To Make Ink: Take four or five ounces of gall, three ounces of vitriol coppresse, two ounces of the whitest gum Arabic, and a quart of middle wort. Beat the gall grossly & put these together into an earthen pot… or glass, & stir them all together with a stick once or twice in each day during a fortnight (Modernized spelling) William Hill Notebook, Beinecke Library.

William Hill Notebook, Beinecke Library

Visit our “secretary hand” page to learn more about reading seventeenth-century handwriting, the alphabet with letters including the ‘thorn,’ abbrevations, and the missing spelling rules and punctuation that made the work of transcribing the letters on the page into a very, very complicated and long process.

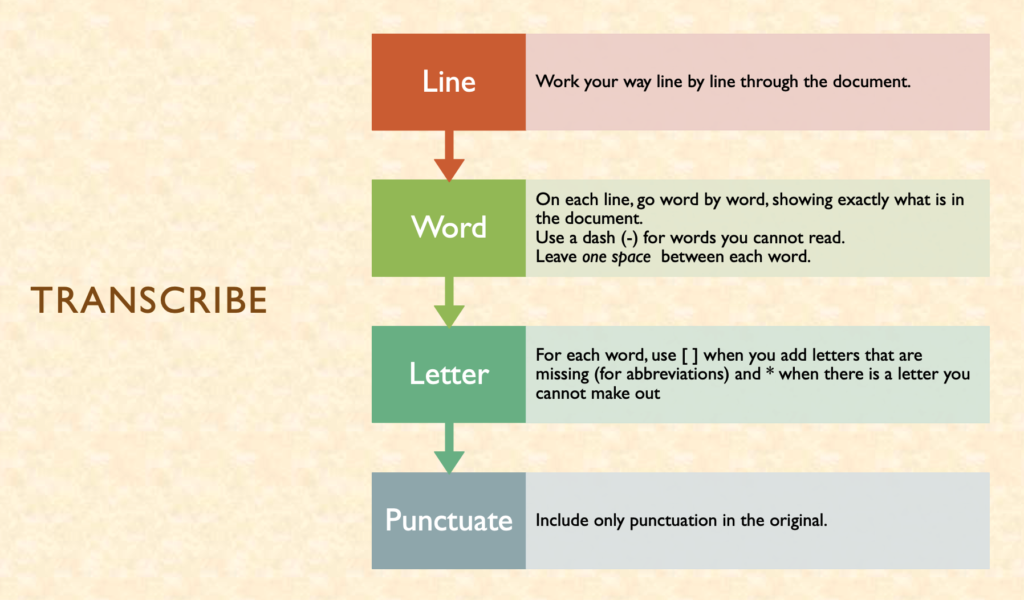

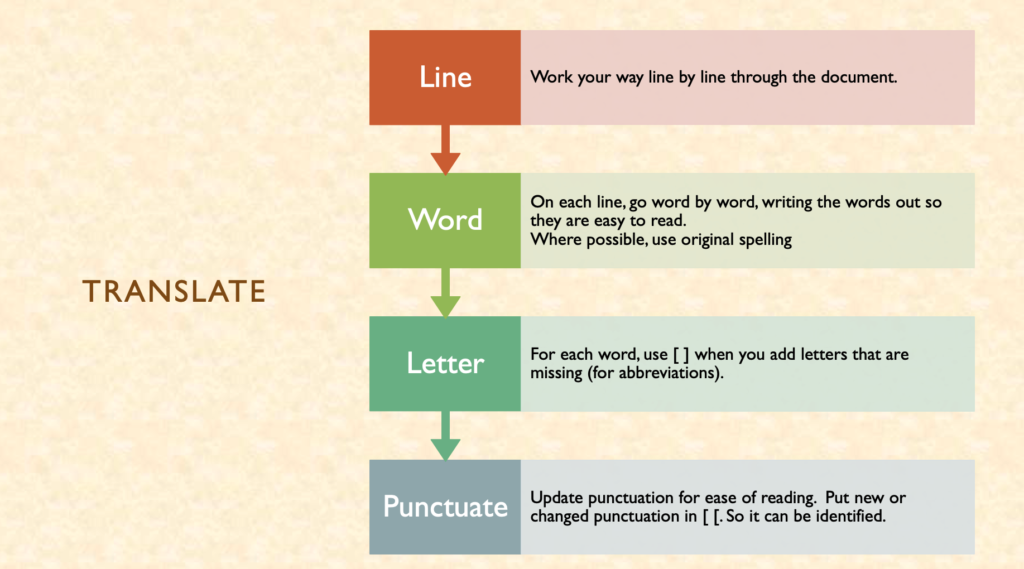

What words are literally on each page?

We read each document letter by letter, putting the letters together into words, the words into phrases and sentences, and the sentences into paragraphs.

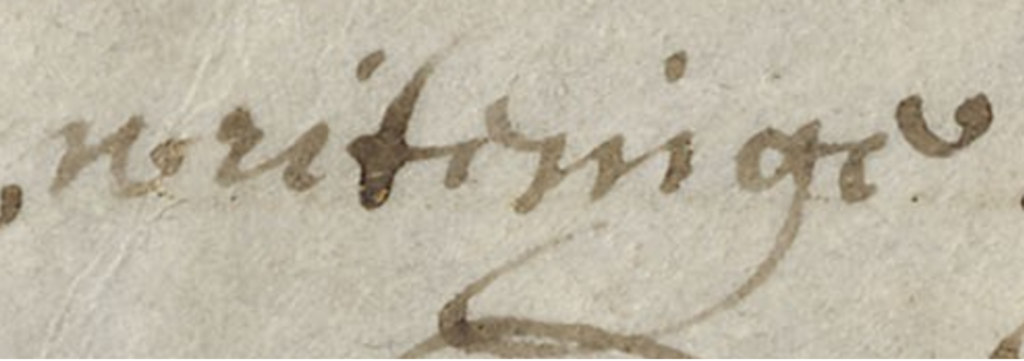

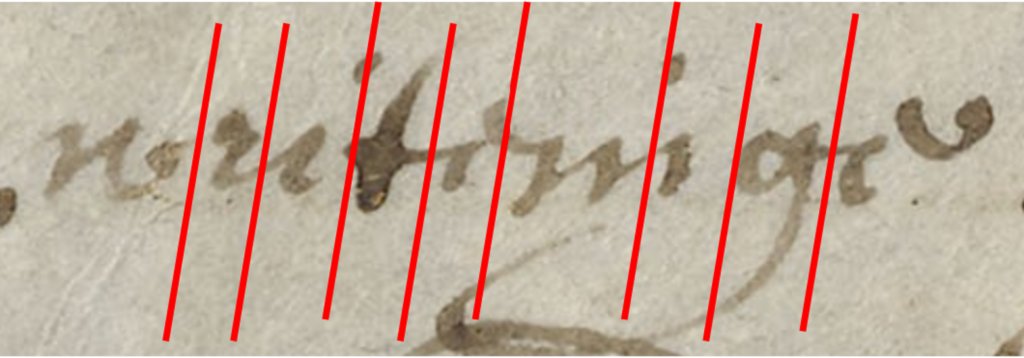

Letter by letter brought words to life.

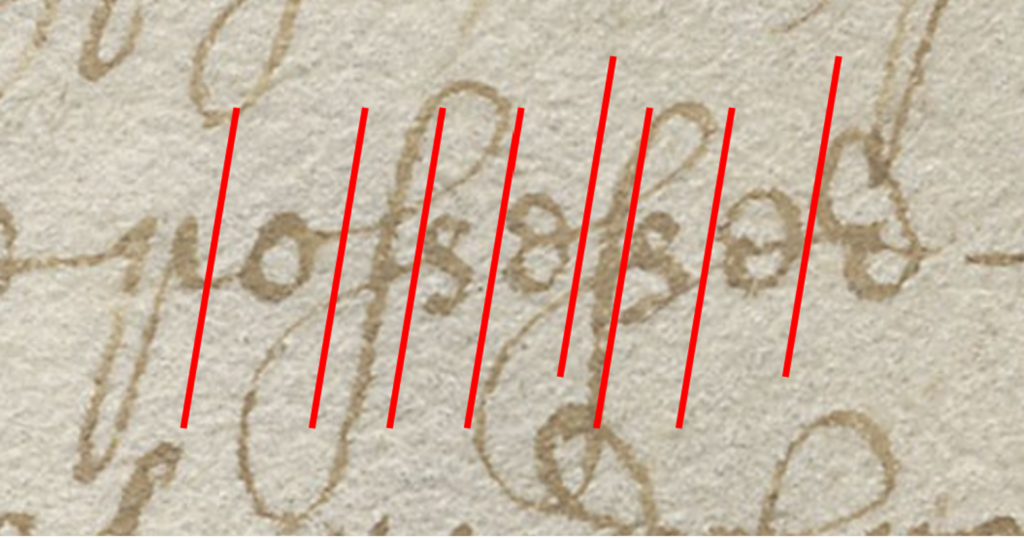

What may first seem impossible to read becomes clear as we work letter by letter.

“writing”

“possessed”

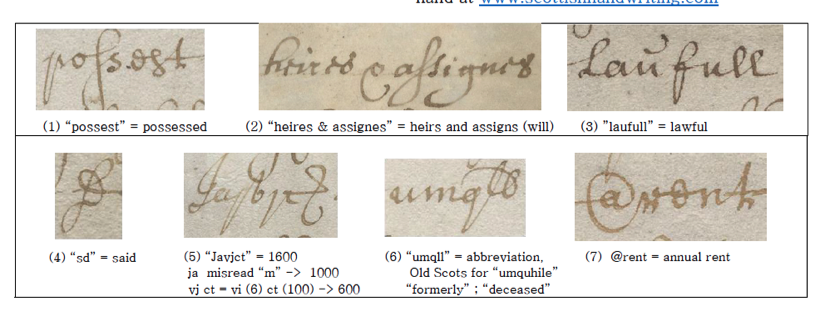

But turning letters into words was complicated for a variety of reasons.

First, in the 1600s, spelling was a challenge. Familiar words sometimes were spelled differently than today, making them hard to recognize. So:

heires & assignes = heirs and assigns (2)

laufull = lawful (3)

possest = possessed (4)

In addition, we found dozens of abbreviations in the sasines. Why would the writer skip the second half of the word? Cutting out letters saved time, space on the page, and reduced the number of pauses for a writer to re-dip a quill in the inkwell. In these documents, frequently used words had abbreviations whether they were short or long.

Three we often saw were:

said → sd (5)

pairts → pts, and instrts→instruments.

Even first names could be abbreviated: Alxr (Alexander) and Wm (William) are two we found.

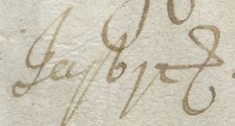

Dates also got abbreviated – but quite differently from 1/1/2023. You may be stumped by what appears to be “jajvjct” (1) in the Scottish sasine.

This strange word mixes Latin and longhand numbers to show “1600”:

jaj → corrupted or misread form of “im” : 1000 (Latin)

vj → the Latin numeral for 6 (v → 5, i/j → 1)

ct → short for the Latin “centus,” 100.

Similarly “umqll” (6) is short for the Old Scots “umquhile” (after a while), meaning deceased.

And there were symbols. These, too, had to be ‘translated’ What looks like a backwards comma is an ampersand (&) (2) What looks like the “@” symbol abbreviated the word “annual.” In a different Scottish indenture, the word “@rent” (7) abbreviates “annual rent”, or the amount a tenant pays a landlord each year.

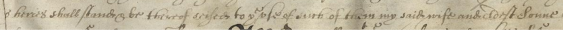

Third, there was almost no punctuation. A few parentheses were included, but no periods or commas. Sometimes extra large capital letters and blank spaces spaces to locate the beginning of sentences. Other times we waited until all the words were written and looked for plausible groupings.

With the English will, once we had the words it was (generally) possible to understand what was on the page… although we did have some legal terms to look up.

To transcribe this line, we start by differentiating these words from one another, identifying words like “heires” “and” “wife” and “sonne.” Then, we filled in missing words: “his heires shall stand & be there of seised to [th]e use of such of them my said wife and elder sonne.”

For the Scottish sasines, the translation was, on the whole, much more complicated.

What do the words mean?

When we set out to work on these documents, we did not anticipate how many forms of ‘translation’ we would encounter. Wentworth’s will was relatively straightforward – despite some abbreviations and legalese. In the Wentworth will, for example, the phrase “Countie of Midd” in England was initially confusing, until we identified the county as Middlesex.

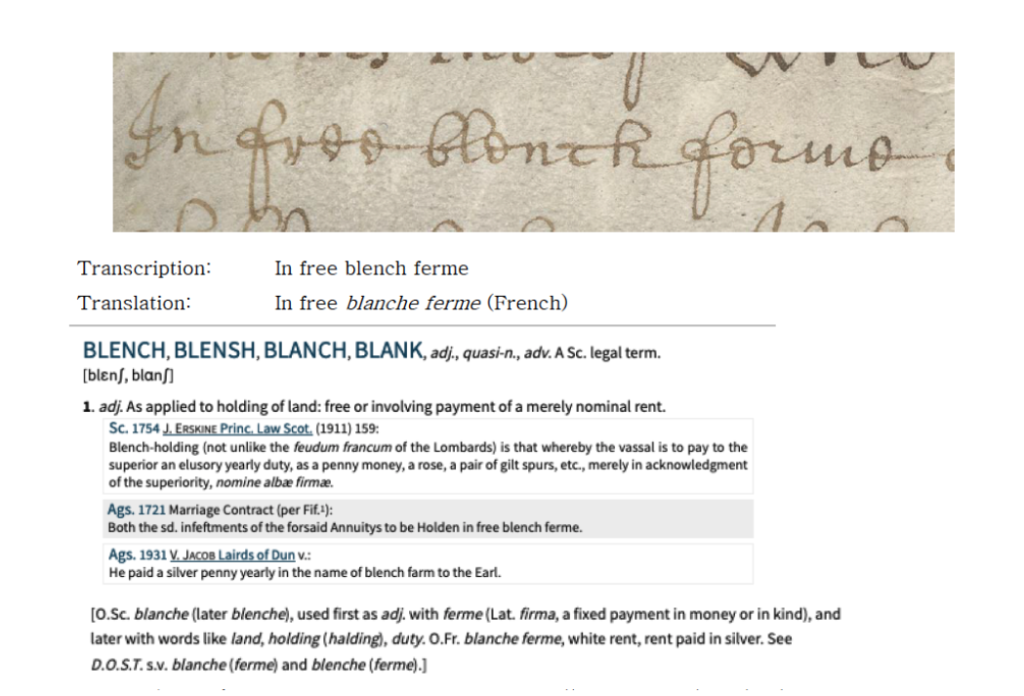

The Scottish sasines, on the other hand offered a significant reading challenge : figuring out whether a strange word was an unusual spelling, an abbreviation, or another language – legal Latin, Old Scots or even French.

As we read the documents, we tried to pronounce unfamiliar words out loud. Sometimes hearing helped us decode the meaning we couldn’t see. “Ane” could mean any or one, so hearing it in context could help us decide which meaning to assign.

More often, however, we did research in dictionaries and histories of early law. Sometimes we looked up words we didn’t think could be real.After seeing “infefting” one too many times, we looked it up, and it meant “giving symbolic possession of inheritable property.”

Other times, we did some research when an easy spelling fix didn’t make sense. Having the phrase “compeared before me” led us to look up “compeired” and find it was not a misspelling of “compared” but a term meaning to “appear in court.”

And even when we figured everything out, we still had to accept that a legal document is a form of communication quite different from conversation.

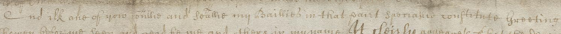

Let’s take a more complicated phrase from a Scottish Sasine

Trust us that it reads….

“[a]nd ilk ane of you iontlie and seallie my Baillies in that pairt speciallie constitute Greeting”

“ilk ane” are old Scots… for “if any”

“iontlie and seallie” are abbreviatiosn for jointlie and severallie, so jointly and severally, or together and individually

a “baillie” is a bailiff, or court official/town magistrate

“specially” is “especially”

The translation

“if any of you jointly and separately my magistrates in that part especially constitute greeting…

still needs a lot of context to really make sense to a non-specialist.